Some characters never truly belong to one era. They return when culture shifts, when love is redefined, when longing learns a new language. Dracula is one of those figures. Watching the 1992 and 2026 versions together feels less like revisiting a story and more like witnessing the same soul live two very different afterlives. One is forged in fire and defiance. The other is shaped by grief, silence, and the unbearable weight of surviving too long.

Gary Oldman’s Dracula storms into the myth with the force of will itself. He is a shapeshifting master—warrior, wolf, bat, prince—commanding the screen through transformation and excess. His romance burns hot, a fever dream driven by a refusal to accept death or divine authority. This Dracula hates God for taking Elisabeta from him and weaponizes his curse in retaliation. Love, for him, is erotic grandeur: lust, hunger, and theatrical power wrapped in Gothic spectacle. Even when he speaks softly, there is a commanding intensity in his voice. His plea to Mina is never neutral—it is the predator’s promise of eternal night and eternal ecstasy, a demand disguised as devotion.

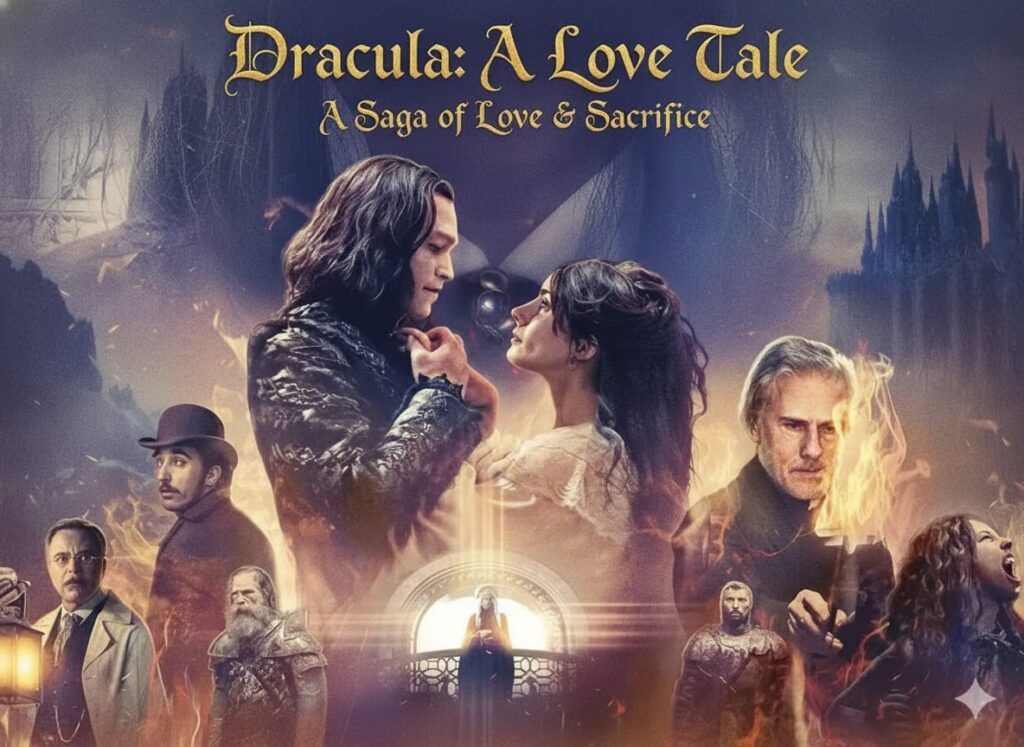

Caleb Landry Jones’s Dracula arrives from the opposite emotional direction. You do not meet a ruler; you encounter a broken recluse. He is unsettling because he is so exposed—creepy, somatic, painfully human. Four centuries of isolation have not sharpened him; they have worn him down. His romance is not a blaze but a hollow ache that has echoed for generations. Where Oldman’s Dracula is active and aggressive, Jones’s is passive and somber. The emotion here is cold—defined by spiritual melancholy, quiet obsession, and heartbreaking loneliness. He fears God rather than cursing Him, and his love for Mina is steeped in shame. He wants to protect her, even from himself. He relies on magical perfume and sentient gargoyles not out of cunning, but exhaustion. This is a man who no longer wants to conquer the world—he wants forgiveness, or failing that, an end.

Their voices tell the story as clearly as their bodies do. Oldman’s dialogue is operatic and iconic, filled with high-stakes proclamations and dramatic shifts in pitch, like a stage performance brought to cinematic life. Jones’s speech is mumbled, intimate, sometimes almost banal, rooted in the mundane horror of living forever. His mangled Central European accent does not crown him as a king; it marks him as a haunted outsider. His words feel like prayers rather than declarations—fragile questions about whether a love that causes so much pain can ever be absolved.

The women at the center of these stories reveal how radically the myth has shifted. In 1992, Winona Ryder’s Mina is otherworldly and fearless, balancing Victorian restraint with a modern sensual awakening. She navigates a dangerous duality—devoted to Jonathan Harker yet magnetically drawn toward forbidden darkness. Her Mina is intelligent, resourceful, a schoolmistress with what the film calls a “man’s brain.” She compiles evidence, undergoes a visceral psychic transformation, and ultimately makes the most agonizing choice of all. It is her hand that releases Dracula from his curse. She is not merely desired—she decides.

In the 2025/2026 version, Zoë Bleu’s Mina exists very differently. Critics have described the performance as one-dimensional, noting a lack of emotional weight or genuine intimacy in her scenes with Jones. The connection often feels hollow, not because the longing is absent, but because the character is rarely allowed to act. She spends much of the film reacting—to perfume, to visions, to memory—rather than driving the story forward. Her identity is so tightly bound to being the reincarnation of Elisabeta that there is little space left for Mina as a person with her own present-tense will. Her fate is ultimately shaped not by her strength, but by theological intervention through the Priest. Agency, once central, quietly slips away.

This shift is mirrored in how the films treat desire itself. The 1992 version embraces erotic spectacle with unapologetic intensity. Bodies writhe, veils billow, and seduction is physical, explicit, and dangerous. The infamous scenes—the brides, the blood-drinking from Dracula’s chest—pulse with sexual tension. Love is framed as a force that liberates characters from Victorian repression into wicked, burning desire. Historically, the film has been read through a male gaze, reveling in stylized excess and carnality.

The 2026 film moves toward a different erotic language. Its tone is often described as a female-gaze romantic epic, prioritizing ache and emotional connection over raw steam. Sensuality becomes melancholic rather than predatory. The seduction unfolds through atmosphere, proximity, and the strange intimacy of a magical perfume that turns desire into something sensory, almost chemical. Love is treated not as liberation, but as a disease of the soul—a fine, incessant rain that soaks into every corner of existence. The longing is there, even the horniness, but it is wrapped in tragic devotion, closer to Romeo and Juliet than Gothic excess. And yet, for some viewers, this restraint leaves the romance feeling oddly soulless, melodramatic, lacking the tension that once made Dracula dangerous.

Nowhere is this emotional cost clearer than in what happens to Jonathan Harker. In the 1992 tradition, the story ultimately restores balance. Mina releases Dracula, the curse lifts, and life continues. The implication—faithful to the novel—is that Mina and Jonathan remain together, building a future, even welcoming a child. Love survives the monster.

The 2025/2026 film refuses that comfort. After the final battle, Jonathan arrives too late. Mina stands holding the ashes of Dracula, fully aligned with her past life as Elisabeta. In that moment, Jonathan understands that the woman he loved is gone—not dead, but transformed beyond return. There is no confrontation, no reconciliation. He simply turns and walks away. The film offers no marriage, no child, no healing epilogue. She is left alone with memory. He is left alone with loss. The separation is permanent, absolute, and devastating in its quietness.

And that is where the sadness finally settles—deep and irreversible.

Oldman’s Dracula dies still burning, defiant, convinced that love means never yielding. Jones’s Dracula survives long enough to learn the crueler truth: that love sometimes means stepping aside, choosing silence, and allowing yourself to be erased so someone else can breathe. The monster who once demanded eternity finally asks for mercy, and when it comes, it comes at the cost of everything he ever wanted.

When the screen fades, it isn’t fear that follows you out. It’s grief. One Dracula wanted the world to kneel beside him in darkness. The other only wanted the darkness to stop. And perhaps that is the most heartbreaking evolution of all—that the moment Dracula learns how to love without possession is the moment he must disappear forever, leaving everyone else to live with what remains.